- Home

- Amin Maalouf

The Disoriented Page 9

The Disoriented Read online

Page 9

When she had finished, Sémiramis looked at her friend out of the corner of her eye. Would he be scandalized, amused, incredulous? Before he could utter a single word, she realized that, mostly, he was angry.

“And all this went on behind my back, as though it had nothing to do with me? You don’t think you should have asked my opinion before telephoning my partner?”

“Absolutely not! If Dolores had said no, I wouldn’t even have suggested showing you the house. After dinner, I’d have kissed you on both cheeks, like I did the night before, and left you to go back to your room.”

“Bravo! You and she get to decide what’s to be done with me, and I don’t get any say.”

“Not true, of course you have a say. It’s not as though I forced your hand. I offered myself discreetly and then left you at the door, literally leaving you an honourable way out; I wanted you to be free to go, right up to the last minute. But you chose to stay with me …”

This was unarguable. Adam laid a conciliatory hand on his friend’s knee.

“That much is true. I freely decided to go up to your room, I accept that, and, if I hadn’t, I would always have regretted it. But I find this conspiracy between you unsettling. ‘Lend him to me and I’ll give him back.’ As though I’m a toy or, as you put it, an outfit.”

“I just wanted to be honest. With Dolores and with you. Do you think it would have been honest for me to take advantage of the fact that her husband is staying under my roof to fulfil a desire I had back when I was a teenager? Do you think I would ever have been able to speak to her again, to hug her like a sister, if I’d allowed lies and duplicity to come between us? And what about you, would it have been honest to welcome you into my bed and then leave you to deal with the guilt on your own? Leave you to carry the burden of the night we spent together as though it were some original sin? To bring years of suspicion and deception between you and your partner? No, I’m not like that. I am a lover with the heart of a friend, it’s important to me that that brief moment of intense pleasure we shared should be a flickering flame in our lives, rather than a shadow. And I expect you to appreciate that.”

Adam remained silent; his hand still lay on Sémiramis’s knee as though he had forgotten it. A puzzled smile played on his lips. His lover carried on:

“That said, if you’re not convinced by my arguments, you can tell Dolores that I made a pass at you and you valiantly rebuffed me. I won’t contradict you.”

He turned to her, seeming to weigh the pros and cons, before concluding:

“I don’t think she would believe me.”

“No, she wouldn’t believe you. In fact, if she did believe you, I’d be very annoyed.”

A moment of silence passed between them. But it was not the same silence. Sémiramis was cool and mischievous; while Adam’s silence seemed onerous and confused.

“Whatever you decide,” she said to him, “don’t feel obliged to phone Dolores right now to tell her about your night of passion. It would be in very poor taste, no sane person wants to hear something like that. What I did, I did not so you would have to say something, but so that you wouldn’t have to say anything. She knows, you know she knows, and she knows you know she knows … There’s no need to explain, to justify, or anything else. Especially not on the phone. Later, in a few weeks, a few months, the two of you might feel the need to talk about it, in the middle of the night, with all the lights off. And each of you can tell the other why you chose to say yes to me … I can tell you right now that the longer, more difficult explanation will be Dolores’s. You, on the other hand, have the perfect excuse: me.”

As she said these last words, she closed her eyes and let her dressing gown fall open. Then she proffered her lips to Adam so that he could plant the kiss that would herald their reconciliation and their belated complicity.

-

2

Once he was back in his room, Adam was nonetheless tempted to call his partner. Not to talk to her about the previous night, which would indeed have been in horrendously bad taste, but because he was in the habit of phoning her every morning and he had no reason not to do so that morning.

He dialled the number, not without a certain apprehension.

“You’re already at the office?”

“I’ve just got here, I haven’t even had time to sit down.”

“So, you’re not in a meeting …”

“Not yet, we’ve got time for a chat. Just give me twenty seconds to put my things down.”

She set down the phone for a moment, then picked it up again.

“Right, I’m all yours. Sémi says you’ve been getting a lot of work done. Maybe even a bit too much.”

“It’s true, I have been getting a lot done.”

“On the biography?”

“No, I’ve put Attila to one side, I’m working on something else.”

“If you’re constantly working on something else, you’ll never finish that biography.”

“Being steeped in the atmosphere of this country again, I had other desires, you can understand that …”

“Yes, I heard a little something to that effect …”

She laughed, and Adam was angry with himself for using such an ambiguous phrase. He quickly explained:

“After Mourad’s death, I felt a need to tell the story of my friends, of my youth, of what time has made of us.”

“I understand, it’s normal to feel a sense of nostalgia at times like this. But I feel like you’re losing yourself … I know you, Adam. You’ll fill hundreds of pages with stories of your friends, but it will all end up mouldering in a drawer … Don’t get me wrong, I’m not telling you not to do it. It’s cathartic, and it’s good for your mental health, because the death of your ‘former friend’ has affected you more than you care to admit. But don’t kid yourself, you’ll never publish it. If only because of your contemporaries …”

“My contemporaries?”

Adam’s surprise was insincere. What Dolores was saying was entirely true. He had a reputation to maintain within the community of historians, one that had taken decades to forge. He was admired for the rigour of his reasoning, his painstaking review of sources, his objective tone, his constant determination to produce something irrefutable, by even the most disputatious of his peers … How could he reconcile the qualities that had made him a respected historian with his desire to relate the existential problems of a group of students? How would his venerable colleagues react? He could already hear them laughing …

“You’re suggesting that I give up, and go back to working on good old Attila?”

“No, that’s not what I’m suggesting, honestly. Given where you are, and given the circumstances, you could hardly carry on working on a biography of a fifth-century conqueror as though nothing had happened. Write what you feel you need to write, do it honestly, think of it as a private memoir. Just remember that it’s an interlude, and as soon as you’re back in Paris go back to working on ‘Atilla,’ finish it, publish it, then you can move on to something else. In other words, allow yourself to stray a little, but not too much, and never lose sight of what is important …”

Adam was about to say that he entirely agreed, but his partner did not give him time.

“Someone’s just knocked on the office door,” she said in a whisper. “They’re here for the meeting.”

She immediately hung up. He glanced at his watch, it was 11:30 a.m. precisely, half past nine in Paris. The time at which his partner met with her colleagues every morning.

Having been hired by a European publishing conglomerate to edit a monthly popular science magazine, Dolores had taken the risk of making it a weekly. She had had a compelling case for her decision, and her bosses had supported her and given her substantial funds. But it was clear, as much to her as to them that, if the project failed to deliver, she would bear the responsibility. Sin

ce then, she had spent most of her time working on the magazine, and even when she was not, she was constantly thinking about it and talking about it with Adam. Not that this bothered him, quite the contrary; in fact, he enjoyed playing the role of her Candide, a friendly advisor with no ulterior motive, unconnected to the magazine and the world of science.

After their telephone conversation, Adam opened his notebook and, pencil in hand, thought about the curious situation in which he had put himself.

TUESDAY, APRIL 24

I still feel worried, even though Dolores was astonishing, a perfect model of good grace and tact.

Not a word about what happened last night, and yet not a word that didn’t touch on it somehow. I don’t know whether each insinuation was carefully rehearsed; and maybe I saw allusions where there were none. But the message is clear: the interlude is acceptable as long as it remains an interlude.

As a code of conduct, it suits me, and I should find the fact that Dolores made it explicit reassuring. But my fears come from elsewhere—from that mundane, tyrannical notion that makes me believe I have committed a sin, one that must, inevitably, be atoned for, for reasons connected both to human nature and the laws of heaven.

My generation, the women and men who turned twenty during the 1970s, made the liberation of the body its central concern—In America, in France, and in many other countries, including mine. In hindsight, I am convinced that we were absolutely right. It is by controlling our bodies that moral tyrannies succeed in controlling our minds. It is not the only weapon they use in order to control and dominate, but, throughout the course of history, it has proved to be one of the most effective. For this reason, the freeing of the body remains, overall, a liberating act. On condition that one does not use it to justify every vulgar kind of behaviour.

What I have just experienced with Sémi has meaning, because it represents a belated revolt against my crippling teenage shyness. Therefore, our intimacy was legitimate. But it will quickly come to seem pathetic if, rather than recognizing it as a nod to our adolescence, my lover and I start treating it as a banal affair, a fumble between the sheets.

An interlude, then, my night with Sémi? Probably. She does not see things any differently. There, the word Dolores used is neither offensive nor shameful.

An interlude, too, all the things I feel the need to relate about my youth, my friends? Yes, that is probably the appropriate word. Nevertheless, it is an interlude I do not intend to bring to a close just yet. Even if the pages dedicated to the memory of my scattered friends are destined to end up in a musty drawer, to be forgotten, they still mean something to me. My life, and that of the people I have known, may not seem like much compared to that of a famous conqueror. But it is my life, and if I truly believe it deserves only to be forgotten, then I did not deserve to live.

-

3

When Sémi came and “kidnapped” me last night, I was in the middle of recounting the kidnapping of Albert and the fears of those attempting to get him released.

Had his abduction and his captivity been a salutary shock to our friend? Had they restored his will to live? There was no way of knowing.

“Might it not be more sensible to leave him there a little longer,” Mourad wondered on the phone. “To be honest, as long as he’s not being mistreated, I’m in no hurry to see him released.”

I completely understood his fears. It was something that had occurred to me the moment I first heard that Albert was being held as a hostage. Was it possible that releasing him might mean delivering him to death, just as those who had abducted him had saved him? The irony of the situation was laughable, but for us, the fear was real.

While we talked, a solution began to form in my mind, one I immediately suggested to Mourad.

“If you manage to get him released, whatever you do, don’t take him back home. Take him to your place in the mountains for two or three days. Then send him here to me, in Paris. After that, I’ll deal with things. Do you think he’ll agree?”

“He has to agree! It’s the only rational solution. If he refuses, I’ll kidnap him myself, I’ll tie him up and ship him to you.”

“Okay, I’ll sign for the delivery.”

I seem to remember that our conversation ended in a gale of laughter that was hardly appropriate to the tragic nature of the situation.

If Adam’s notes and Tania’s recollections are to be believed, this is broadly how things eventually played out. But not without a few last-minute hitches.

When he was released by his unfortunate kidnapper, Albert was left on the outskirts of his neighbourhood; Mourad and his wife, who were waiting a few minutes away, picked him up to drive him directly to their house in the village. The survivor seemed calm, as though he had never contemplated suicide, had never been held hostage. He was taciturn, but cheerful.

In the days that followed, Mourad arranged a passport from the Sûreté Générale and a visa from the French consulate, then bought Albert a one-way ticket to Paris.

Even so, there were some worrying moments. The first came on the day after his release, when the former hostage insisted on being taken back to his apartment. His friends feared that he still intended to take his life, but they could hardly say no. Mourad gave him the new keys, since the locks had had to be changed after he forced the door. Tania drove him into the city and suggested that she go upstairs with him; he firmly replied that he wanted to go up alone and she did not insist; the idea of climbing six flights of stairs was not exactly appealing, and besides, she thought, if Albert was intent on taking his own life, they could not stop him indefinitely. So she waited outside the building for three-quarters of an hour, counting the minutes and imagining the worst. But in the end, he reappeared, looking gloomy and carrying a small suitcase.

The other moment of panic occurred on the day the former hostage was due to catch his plane. Adam recounts it in his notebook.

Albert announced that, before going to the airport, he wanted to go and visit his kidnapper to say goodbye. He had promised the man, and there was no question of him reneging on his promise. Unable to dissuade him, Mourad and Tania decided to go with him.

The mechanic’s house was at the far end of a cul-de-sac; the only access was via a dirt road that the previous night’s rain had turned into a quagmire. The walls were the colour of concrete, as though no one had ever considered painting them. The little yard was piled with old tires.

“The man and his wife were waiting for us. They are decent people whose whole lives revolve around the garage. And, of course, around their only son, whose face is everywhere, in framed photographs, and in the missing-person posters they had printed when there was still hope. Their living room is like a shrine to the memory of the child they lost.

“Tania and I offered our condolences. Their response was polite, dignified, as befits people in mourning. Then the father, his lips quivering, whispered: ‘None of this is your fault!’ And, when Albert stepped forward … You should have seen it! The man took one arm, his wife the other, and the two of them hugged him. ‘You take care of yourself!’ ‘Promise us you won’t do anything foolish.’ ‘Life is precious.’ They started to sob. Albert burst into tears. So did Tania and I.

“When we got up to go, they started again. ‘Come back and see us soon’ and ‘Take care of yourself.’ Albert promised that he would; he swore. He was more upset than anyone—he was still crying as I drove him to the airport.”

“But he did catch the plane?”

“Yes, he caught the plane, thank God. Tania and I have been waiting here at the airport for the flight to take off. Then we phoned you. It lands in Paris at about half past three.”

“Perfect. I’ll have a quick lunch and then go and meet him.”

On the Levantine end of the line, I remember hearing a long sigh.

“We’re pretty relieved to be palming him off on you. Good luck.

”

Remembering Mourad’s words, his voice, his laugh, his determination to save Albert, the extent of our complicity, I cannot help but think that, at this very moment, he is lying in a coffin waiting to be put in the ground. Writing down our conversation suddenly seems to me like a homage to the friend I lost.

Would this discreet homage, made in the privacy of these pages, assuage my guilt or, on the contrary, exacerbate it to the point where I might reconsider my decision about his funeral?

No, I feel no desire to go to it. If there is to be a posthumous reconciliation between the two of us, it will not take place in public, with a microphone in front of me, but in quiet contemplation, amid the whispering of souls.

Samarkand

Samarkand Leo Africanus

Leo Africanus The Disoriented

The Disoriented The Crusades Through Arab Eyes

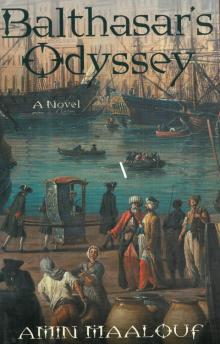

The Crusades Through Arab Eyes Balthasar's Odyssey

Balthasar's Odyssey